Menu

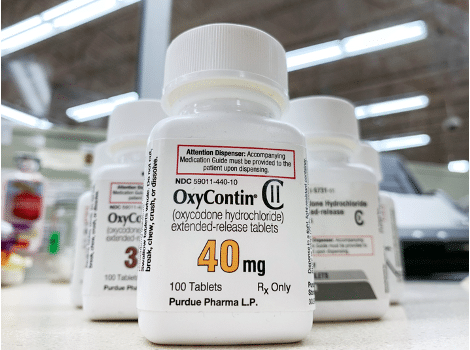

Federal Circuit Affirms that Purdue’s OxyContin Patents are Obvious

May 7th, 2025

The Federal Circuit has affirmed a district court judgment finding that Purdue Pharma’s patent claims to crush-resistant and low-toxicity OxyContin were invalid as obvious.

The case involves patents related to Purdue’s formulation of extended-release oxycodone, sold as OxyContin.

Oxycodone was first developed in the 1910s. In the 1990s, Purdue developed an extended-release formulation, which was approved by the FDA in 1995.

As the court noted,

Unfortunately, oxycodone has become one of the most frequently abused prescription medications, and some formulations can be dissolved and injected intravenously.

According to the US Justice Dept.,

Individuals of all ages abuse OxyContin—data reported in the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse indicate that nearly 1 million U.S. residents aged 12 and older used OxyContin nonmedically at least once in their lifetime.

OxyContin abuse among high school students is a particular problem. Four percent of high school seniors in the United States abused the drug at least once in the past year, according to the University of Michigan’s Monitoring the Future Survey.

Long-term abuse of the drug can lead to addiction, with dangerous effects:

Individuals who take a large dose of OxyContin are at risk of severe respiratory depression that can lead to death. Inexperienced and new users are at particular risk because they may be unaware of what constitutes a large dose and have not developed a tolerance for the drug.

In addition, OxyContin abusers who inject the drug expose themselves to additional risks, including contracting HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), hepatitis B and C, and other bloodborne viruses.

Purdue noted that

The original [OxyContin] tablets could easily be crushed and then snorted or injected to produce an immediate high, causing severe risks of addiction, overdose, and death.

The patents at issue in the case attempted to address these problems.

In 2007, according to the National Institutes of Health, a Purdue affiliate, along with three company executives, pled guilty to criminal charges of misbranding OxyContin by claiming that it was less addictive and less subject to abuse and diversion than other opioids, and were required to pay $634 million in fines.

The Purdue Abuse-Deterrent Patents, which share a common specification, claim a “formulation of oxycodone using the polymer polyethylene oxide (‘PEO’).”

In August 2020, Accord Healthcare, Inc., submitted an Abbreviated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) for approval to market a generic version of OxyContin. Purdue then filed suit in October 2020, asserting that Accord had infringed the patents at issue.

The district court held that all asserted Purdue patent claims were invalid as obvious in light of prior art references.

The district court summarized the dispute as follows:

The parties disagree about whether a [person of ordinary skill in the art] would have been motivated to make PEO tablets with sequential compression and heating, and whether there would have been a reasonable expectation of success in doing so. Second, no prior art used the same combinations of curing time and temperature ranges as those disclosed in the Abuse-Deterrent Patents. The parties disagree about whether routine experimentation by a [person of ordinary skill in the art] would have yielded the times and temperatures disclosed in the patents.

The district court found that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have had a reasonable expectation of success in producing hardened tablets with sequential compression and then heating the tablets.

As to the times and temperatures for curing tablets, the district court found, based on expert testimony, that the times and temperatures recited in the patents’ claims would have been the “product of routine experimentation.”

Thus, the district court concluded that the Abuse-Deterrent Patents would have been invalid as obvious over the prior art.

The circuit court noted that

Obviousness is a question of law, reviewed de novo, based upon underlying factual questions, which are reviewed for clear error following a bench trial.

Also,

The presence or absence of a motivation to arrive at the claimed invention, and of a reasonable expectation of success in doing so, are questions of fact.

With respect to the latter, said the court,

A factual finding is only clearly erroneous if, despite some supporting evidence, we are left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been made.

Under 35 U.S.C. § 103, said the court,

A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained . . . if the differences between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention . ..

Obviousness is based on underlying factual findings, including:

- the level of ordinary skill in the art;

- the scope and content of the prior art;

- the differences between the claims and the prior art; and

- secondary considerations of nonobviousness, such as commercial success, long-felt but unmet needs, failure of others, and unexpected results.

On appeal, Purdue argues that the district court made an improper “inferential leap” in determining that a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine two prior art references with prior art involving ovens.

The circuit court agreed with the district court that “[i]t is not much of a leap to infer that ovens would also be useful for applying heat to harden the matrix tablets.”

For example,

The court relied on multiple factual findings that all support the conclusion that it would have been obvious to try ovens for heating tablets. For example, Accord presented expert testimony on the availability of ovens and the prior use of ovens to heat tablets (including matrix tablets made from several different polymers), and “[prior art reference] Shao specifically taught that the heat curing made its tablets harder.”

Purdue also argued that the district court erred by relying on the doctrine of “routine experimentation” to find that the time and temperature limitations of the Abuse-Deterrent claims would have been obvious.

The district court noted that the heating time ranges in the patents overlap with those in the prior art. For these and other reasons, the circuit court affirmed the district court’s judgment of non-infringement.

Categories: Patents